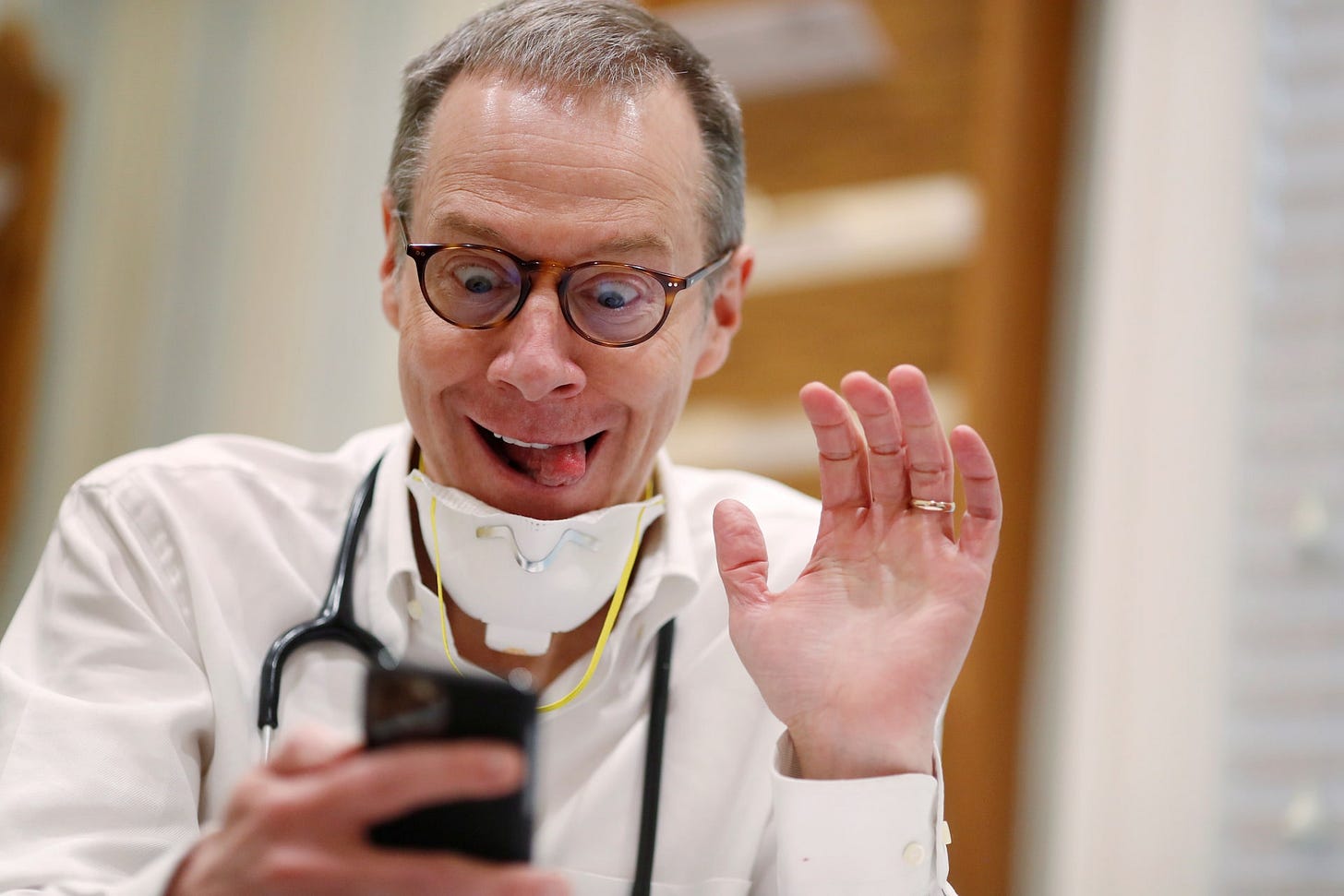

The Art of Care: Photography and Medicine with Dr. Greg Gulbransen

The Long Island pediatrician and photographer on healing, light and perspective

Years ago, Dr. Greg Gulbransen lost his son Cameron in a tragic accident—he ran him over in their driveway, unable to see behind his SUV because there was no backup camera. Today, the same tool—a camera—has become his way of seeing more clearly, capturing the lives of others in pain and using photography to serve, bear witness, and heal.

Greg, a longtime pediatrician based in Oyster Bay, New York, works six or seven days a week seeing patients, but in the moments in between, he’s become a documentary photographer, capturing the beauty and the hardship of life in West Virginia, the Bronx, and beyond. He’s working on several projects, including one on fentanyl addiction and another on childhood poverty in Appalachia.

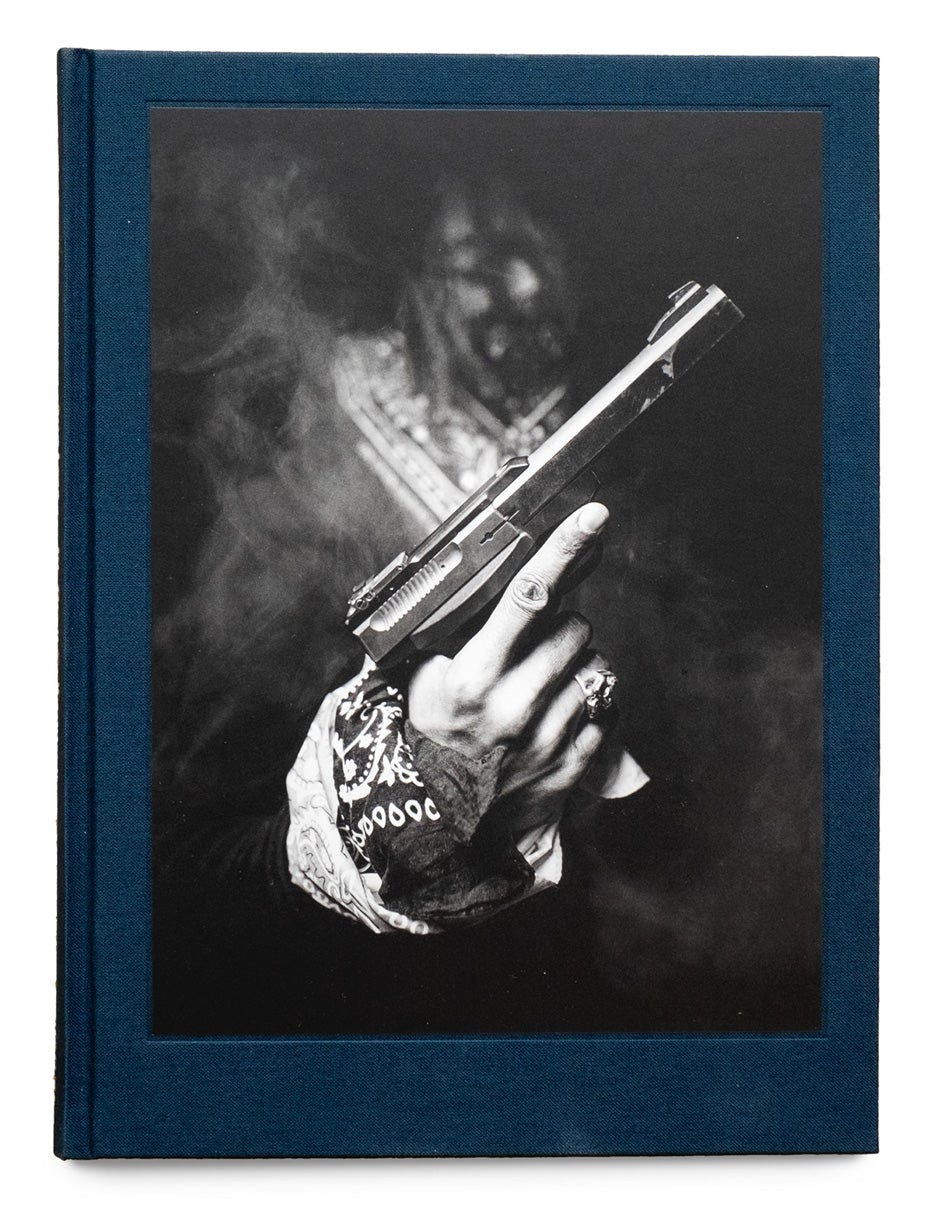

Greg documents stories that have important public health significance to youth in America. With a deep interest in public health issues affecting youth, Greg set out to document the leading cause of death among young people in America today: gang violence and gun-related deaths. His recent photobook, Say Less, published with the help of photo legend Ralph Gibson, documents young people affected by gun violence in the Bronx.

The story focuses on the life of Malik, a leader of a Crip set in the Bronx who lives as a paraplegic after surviving a shooting. Malik, a father to a three-year-old son, relies on daily medical care and support from both his gang members and family while living in public housing near the territory of the rival gang that targeted him and his friends. Though they come from vastly different backgrounds, Greg saw in Malik a reflection of his own inner struggles—an acknowledgment that both men carry their own demons.

In this conversation, Greg opens up about how photography became a way to manage his grief after losing his son, why he always carries prints to give back to the people he photographs, and what it means to “tell stories that matter.”

You’re working full-time as a pediatrician. How did photography become part of your life?

I didn’t pick up a camera seriously until 2014. Years after my son Cameron died, I needed something to help manage the stress. I started photographing birds—snowy owls on the beach mostly. I’d go out after work or early on the weekends and spend hours by the ocean.

Eventually I started joining wildlife workshops, then shifted into fashion and beauty photography. I was published in magazines like Elle and Marie Claire. But I didn’t feel like I was making much of a difference. I wasn’t in charge. It didn’t matter.

I wanted to photograph people, to tell stories that meant something. That’s when I found my voice.

Was that the start of your book Say Less?

Not directly. I started photographing kids in the Bronx who ride in large bands of bicycles across the city through Brooklyn, Queens, all over. I’d ride with them, get to know them. Over time, I saw how the issue of guns and gang violence was becoming more prevalent in the same neighborhoods.

I never intended to turn it into a book. I just wanted to document what I was seeing. But when I showed the work to art photographer Ralph Gibson, he stopped me and said, “You have a book here.” That’s when it clicked. He introduced me to the editor Bill Shapiro, and suddenly it became a real project.

You said earlier that you're often in the photos, even if you're not in the frame. What did you mean by that?

Ralph told me that. I said, “I’m just an outsider.” He said, “No, you’re in the pictures.” And I realized he was right.

This work is deeply personal to me. I’m a pediatrician, a father, and someone who’s experienced loss. I’m not photographing from a distance. I’m trying to care for people, to honor them.

That’s especially true in West Virginia. I’ve been photographing a family down there since the beginning of COVID—four kids being raised in a drug-infested trailer park. Beautiful children. The mom was 15 when I met her. Now she’s 24. I go down several times a year, drive all night, stay a day or two, then come back. It’s exhausting but meaningful.

That’s one of your current projects, right? Along with your work on fentanyl addiction in New York?

Yes, I’m working on a series called Sky High about people addicted to fentanyl who are living on rooftops in the Bronx. Many of them are white, from the suburbs, and their stories are all different: OxyContin, weed, trauma, abandonment. They’re now using a drug called “tranq,” which started in Kensington, Philadelphia, and is spreading everywhere.

So between Say Less, West Virginia, and Sky High, I’m trying to tell stories that relate to public health and youth in America: guns, drugs, poverty.

You’ve talked about wanting to help children at all costs. Where does that drive come from?

It goes back to my upbringing. My parents were community advocates. My dad, a World War II veteran, used to bring kids from the projects to local track meets. My mom raised five boys and always put others first.

And of course, there’s my son, Cameron. After losing him, I decided I would do anything to help a child. I mean that. Anything.

You were instrumental in a national policy change after Cameron’s death. Could you explain what happened?

Cameron was killed in our driveway. I accidentally backed over him. There were no rearview cameras in cars back then.

Soon after, I joined forces with Jeanette Fennell, who had survived a horrific kidnapping years earlier and had successfully advocated for trunk release handles in cars. Together, we fought to make rearview cameras mandatory in all vehicles. It took years—and a lawsuit against the Department of Transportation—but we won. The law is called the Cameron Gulbransen Kids Transportation Safety Act.

Now, every new car sold in America comes with a backup camera. It’s not about my son. It’s about preventing this from happening again.

Do you keep reminders of Cameron close by?

He’s with me all the time. I don’t need pictures on the wall to remember him, though I have them. I carry him in my head. I try to live in a way that wouldn’t create more “luggage,” as I call it. More emotional baggage. I use him as a check. Would Cameron be proud of this? Should I do this?

Your photography feels like a continuation of that commitment. How do you build trust with people in such vulnerable environments?

It takes time. Years. Relationships. If you walk into the Bronx with a camera and no connection, it won’t work. You have to know people, show up consistently, bring back prints, and listen to them.

One of the most important people in my work is Pastor Tony James. She runs a church in the South Bronx. She told me, “I don’t care if you’re white. We all bleed the same blood. Somebody’s got to tell the story.” She introduced me to her congregation and clarified that I was there for the right reasons. That meant the world to me.

Do you ever feel unsafe on assignments? Or hesitant?

Sometimes, sure. I keep my head on a swivel. I play loud music when I drive in. I walk in the middle of the street if I sense something’s off. But the relationships I’ve built—people saying “he’s good, leave him alone”—they matter.

Let’s talk about photography more directly. What does it give you? What does it do for you?

It preserves time. That’s a big one. I never got to say goodbye to Cameron or to my dad. My dad came to my office one day out of the blue, and I barely noticed him. He looked back at me as he walked out the door and said, “You did well for yourself.” The next day, he dropped dead.

So I decided: I want to preserve people. I want to remember.

Photography also gives me peace. It helps me process. Editing photos at night, with music on, is one of my favorite things to do. And when I get a great shot? That high lasts for days.

What’s your process like? Are you constantly carrying a camera?

Not all the time. But when I go out with a purpose, I’m ready. I don’t shoot casually anymore. I only photograph when I’m telling a story.

And I always bring prints. If I take your picture in the Bronx, you’ll probably get a mounted 13x19 print. People deserve that.

How do you balance the emotional toll of it all—your medical practice, the photography, Cameron, and the weight of the stories you tell?

You learn to compartmentalize. I’ve been a pediatrician for decades. I’ve seen it all. You don’t carry every case home with you. You can’t.

The same goes for photography. I don’t cry when I see something terrible. I react. I care. But I don’t crumble. That’s not helpful to the people I’m trying to serve.

What are the most common issues facing kids today?

Mental health, hands down. Anxiety is through the roof. Especially among teenage girls. I probably write more prescriptions for psych meds than antibiotics these days. That never used to be the case.

Why?

Social media, phones, COVID—it’s all created this perfect storm. Everybody looks like they’re doing great online, but they’re not.

Do you imagine doing photography full-time someday?

Maybe. I’m 62 now. I still love being a doctor. But eventually, I think I’ll focus more on storytelling, on teaching others how to gain access, how to build trust, how to be useful. Because at the end of the day, that’s what matters: being useful, telling stories that matter, helping people.