Jim Coleman: Restoring a Legacy, One Organic Acre at a Time

Fueled by faith, grief, and purpose, one man is proving that farming is about healing, hope, and generational change

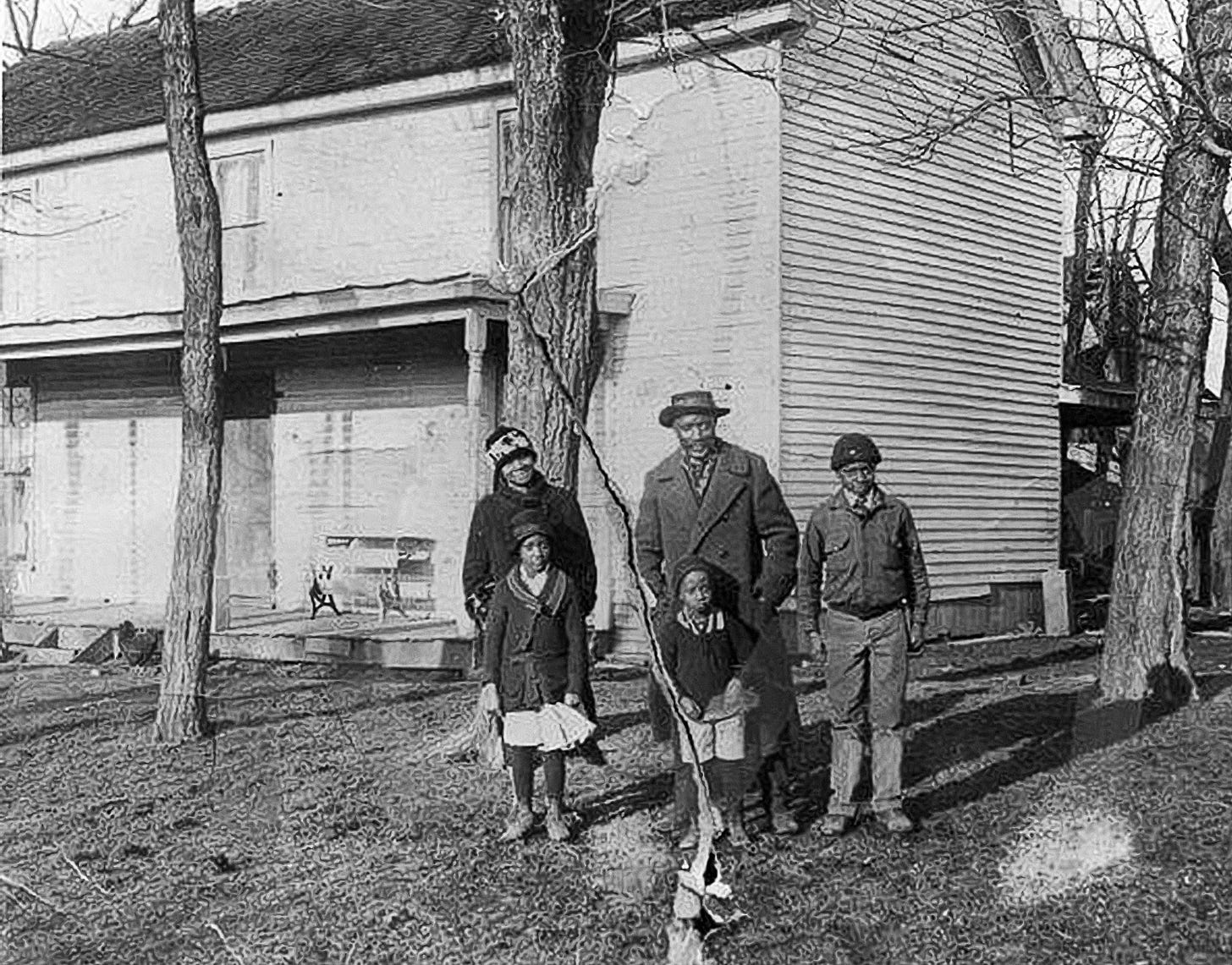

In the 1880s, Jim Coleman’s great-grandfather—born into slavery—returned home to Lexington, Kentucky, after serving in the Union Army during the Civil War. Then he bought the very land he had once worked as a slave, thanks to a small loan from the United Benevolent Society, a community-run Black-owned bank. That 13-acre farm, Coleman Crest, would go on to send five of Jim’s aunts and uncles to college.

Over a century later, in 2020, Jim lost his wife, Cathy, of 37 years, to breast cancer. Months later, he stood in front of 200 masked guests and TV cameras and announced the restoration of his family’s historic farm.

“I was living in Scarsdale, New York, paying nearly $40,000 in taxes, commuting hours a day, and grieving the loss of my wife, Cathy,” Jim says. “Our farm had grown wild and unused…I buried Cathy alone during COVID. I gave the eulogy and produced the programs. It was the darkest valley for me. I had a choice: become depressed or pour myself into something positive, and the farm was calling me. It was overgrown and abandoned. I needed healing—and it needed restoration.”

He founded Coleman Crest Farm, the first Black-owned certified organic farm in Kentucky. After a successful corporate career working for companies like American Express in cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, Jim returned to his family farm in Lexington for what began as a personal restoration project but has since grown into a movement.

At 64, he isn’t slowing down. Jim is raising a private equity fund to purchase and convert 200 conventional farms into certified organic operations, aiming to hire thousands of workers and produce millions of pounds of healthy food. His vision? Clean food, second-chance employment, and a new regenerative agriculture model that honors people and the planet. He’s passionate about food equity, especially for groups that don’t have easy access to healthy food. His produce feeds food pantries. His scholarships honor his late wife. And his story, rooted in the legacy of a great-grandfather who bought the land after serving in the Union Army, proves that healing the soil can also heal the soul.

Fueled by faith, grief, and purpose, Jim is showing that farming can be about healing, hope, and generational change.

You first took over managing the family farm when you were just 12 years old. What happened?

My father came home one day and said, “Your brothers and sisters are in college. Your mother’s going back for her master’s. I’m working at the post office at night. I need you to step up.” I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “You’re the manager.” I asked what the pay was. He said, “Three hots and a flop”—three hot meals and a bed.

That’s quite a promotion. How did you handle it at that age?

I realized the pigs kept breaking out of the pen, so I asked my dad why. He said we couldn’t feed them enough with what we were growing. So I tripled the amount of corn we bought, and guess what? The pigs stopped escaping. They were growing faster than ever. My dad came home and said, “These are the biggest hogs we’ve ever had.” I said, “That’s because I’m doing my job.” He said, “You are, but you’re going to break us.”

So what did you do?

I said, “Why don’t we sell the pigs?” He looked at me and said, “Don’t sell the goose that lays the golden egg.” Two days later, he signed a contract with a local restaurant to pick up their leftover food scraps. They paid us five dollars a barrel. That became feed. Then we had too much slop. So my dad said, “Go sell the extra to other farmers.” I did, for five bucks a barrel. That money paid for my first three years of college.

You ended up at Howard University. But you didn’t get in at first, right?

They rejected me. My mom wouldn’t accept it. She wrote a letter to the president of the university. Later, they reversed their decision and said I could attend under conditional reinforcement. I had to take a summer class at the University of Kentucky to prove myself. I got an A, and I was in.

I showed up with a $10,000 check, including $5,000 saved from managing the farm. Two years later, I was elected student council president. And the woman who helped hand out my flyers? That was Cathy, my future wife.

How did you meet her?

The first time I saw her, I was playing paper football in the library. She walked in, and I turned to my friend and said, “Who is that?” He said, “That’s Cathy Clash —engineering major. Brilliant. Gorgeous. She’s not for you.” I watched her for a year before I got the courage to talk to her. Eventually, I invited her to help with a student council campaign. I called her that night, took her to lunch the next day—and we never stopped talking. That conversation lasted 37 years.

What was it like transitioning from your corporate career back to the farm?

After Cathy passed, I couldn’t do it anymore, over $30,000 in property taxes, the daily grind in New York. I was grieving, and I needed a purpose. The farm had turned into a jungle, overgrown and forgotten. I poured everything into it: money, time, heart. It became my therapy. It saved me.

What did the early days of the farm restoration look like?

It started with a community event called Restoration Day. Over 200 people showed up: mayor, city council, fire chief, media. I announced that I was restoring Coleman Crest Farm and working toward USDA organic certification. Two days later, I got a call from a local organic farmer. She and her husband mentored me and introduced me to their son, Grant. I hired him as my farm manager. That accelerated everything.

You’ve shared that your great-grandfather, who originally bought the land, was a Civil War veteran. Did you always know that?

I only found out in 2023. He was born into slavery on this very land. At 19, he enlisted in the Union Army and fought in the pivotal Battle of Milliken’s Bend in Louisiana. When he came back, he and his wife borrowed $1,200 from the United Brothers Benevolent Society—a Black-run cooperative lending group—and bought the farm in 1888. It’s been in our family ever since.

What are you growing now?

Okra, tomatoes, carrots, cucumbers, squash, red potatoes, and more. Last year, on just 1.4 acres, I did $62,000 in gross sales and produced 12,000 pounds of produce. Most of it (95%) went to food pantries through a USDA program. Next year, I plan to expand and build hoop houses for year-round farming.

Who are you hiring to work these farms?

Second-chance workers, H-2A visa holders, young people, and people with special needs. I want to open doors for folks who’ve been overlooked. Everyone deserves a second chance. I’m also hiring women. They’re leading this movement.

How are you preparing for such a large operation?

I partnered with the University of Kentucky. Their capstone agriculture students helped me create criteria for which farms to buy—soil quality, access to water, zoning, and proximity to markets. We identified 14 potential farms and narrowed them to four initial purchases. We’re installing wells, irrigation systems, hoop houses, and on-site housing for workers.

You also launched a scholarship fund in Cathy’s honor?

Yes, after she passed, I donated $1.5 million to the University of Kentucky’s College of Agriculture. It’s in a trust. When I die, it’ll continue to support disadvantaged students who want to learn agriculture and make a difference. My dream is to leave $25–30 million to the school by the time I go.

Why at the University of Kentucky?

She believed in education. She had degrees in engineering and business, worked at Oracle, and was ahead of her time in tech. The scholarship supports disadvantaged students, especially Black youth who want to make a difference through farming.

How has your health and outlook changed since returning to the farm?

Night and day. I sleep better. I’m outside every day, walking 10,000 steps, eating clean. I work with my team in the field, then hit the gym three times a week. At 64, I’m healthier than ever. The farm healed me, body and soul.

What do you say to people who might feel stuck in life? A little gardening can go a long way.

There’s freedom in farming. If you’re paying $4,200 for an apartment in a place like New York, you could buy a ranch and 15 acres in Kentucky for the same. Work remotely. Grow your food. Build wealth and peace.

You’ve come a long way, starting as a 12-year-old farm manager to Fortune 500 executive, entrepreneur, investor, and farmer. What’s the through-line?

Perseverance. Smart thinking. Creating win-wins. My dad always taught me: don’t sell the goose that lays the golden egg. That lesson saved the farm once. It’s going to help transform American agriculture now.

Now you’re planning to buy more farms?

Yes, I’ve created a private equity fund. The goal is to buy 200 conventional farms—about 50,000 acres—and convert them into certified organic farms. We’ll hire over 10,000 workers, 600 managers. I’ve got strong investor interest, including a wholesaler who’s offered to buy millions of dollars worth of produce from us.

Are investors on board?

Yes. We’re going to ship across the country and the world. There’s massive demand. People want clean, safe, local food.

What’s the bigger picture behind this mission?

Only 1.2% of farmland in the U.S. is certified organic. Meanwhile, demand for organic food is skyrocketing. We’re importing a lot of food with questionable practices. Local, organic food shouldn’t be a luxury. It should be a right.

We’re not just growing food. We’re rebuilding lives, reclaiming land, and proving you can do good and do well.

What does a good day on the farm look like now?

I wake up at 4:45. I write the plan for the team, buy breakfast for everyone, and we talk about our goals. We work the land, then eat lunch together. I usually fall asleep by 9. I also hit the gym three times a week. At my age, you’ve got to stay strong if you’re working in the field.

What do you hope people take away from your story?

That anyone can be great because anyone can serve. You don’t need a PhD. You need a heart full of grace and a soul powered by love. That’s how my great-grandfather bought this farm, and that’s how I’m going to leave it.

I worked with Jim

At Amex for a short time. Sorry to hear about his wife’s passing.