Inside Voices: A Few Lessons from the Prison Journalism Project

What I’ve learned volunteering as a writing coach for people in prison

Hi friends,

I can remember the sound of my heartbeat as I stepped through the big doors of Great Meadow Correctional Facility, a now-closed maximum security prison in Comstock, New York, about 70 miles north of Albany. It was rural, chilly, and the building itself looked like it hadn’t changed much in decades: layers of concrete, wire, and rules. I was nervous.

The guards told me I couldn’t bring anything in, except for my tape recorder. Not even a pencil, which is too sharp, too risky. I was there to interview a former Syracuse football player who, years earlier, had stabbed a teammate. I wasn’t there to justify it or defend him. But we had been writing letters to each other for months, and I just wanted to understand how he was doing, years into his sentence, and to share his story as honestly as I could.

After being checked in, I was escorted into a stark visitor area. My chest was still pounding, and I was afraid I would do something that violated the rules. But once we started talking, the tension gave way to something else: curiosity, conversation, connection.

That experience stayed with me and, in many ways, it led me to some of the work I do now.

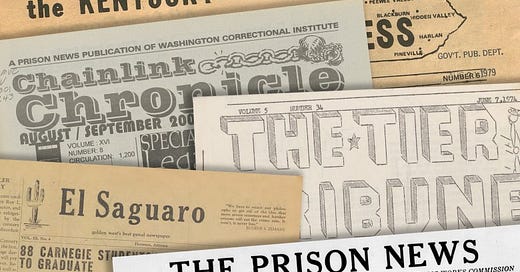

For about a year, I’ve volunteered as a journalism coach for the Prison Journalism Project (PJP), a nonprofit that helps incarcerated people find and share their voices through writing. The mission is simple and powerful: elevate stories from within the justice system, and in doing so, challenge the way the public views incarceration and those who live through it.

PJP is “bringing transparency to the world of mass incarceration from the inside and training writers to be journalists, so they can participate in the dialogue about criminal legal reform. Our approach also provides workforce readiness training, so they can be better prepared to re-enter society even as they’re shifting the narrative.”

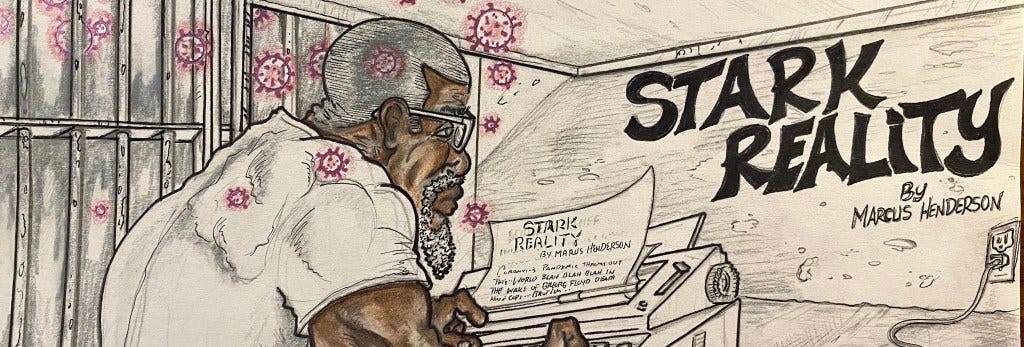

I’ve had the privilege of working (remotely) one-on-one with writers from across the country. Many of them have no formal writing background. Some have never told their story to anyone. But all of them have something to say, and once they find the words, it’s impossible to look away.

A few stories that have stayed with me:

One writer trains service dogs in prison, forming deep bonds with animals that go on to support veterans and people with disabilities, among others (dogs are amazing creatures). He writes about what it means to be trusted again and loved unconditionally, even if only by a dog.

Another writer was mistakenly called before the Parole Board and issued a three-year deferment. When he pointed out their error, the Board punished him with a five-year deferment instead. He’s writing through the betrayal and confusion of being penalized for telling the truth.

One man is documenting his journey toward self-worth, learning that he has value beyond his sentence. His piece on self-care, purpose, and mental health behind bars was raw and honest.

And then there’s a woman who struggled in school as a child, partly because her mother couldn’t read or spell. Now, she’s part of a prison education program through Penn State, where incarcerated tutors are paired with incarcerated learners. She’s reclaiming her education and her confidence.

These are just a few of the kinds of stories PJP exists to tell. They’re stories you don’t typically hear on the news. Stories that humanize, complicate, and connect.

And they matter. Not just for those on the inside, but for us, too.

If you want to read more or support their mission, visit prisonjournalismproject.org. You can read the stories, share them, donate, or even get involved as a volunteer.

I’ve learned a lot in this work. Mostly, storytelling is one of the few tools powerful enough to reach across concrete walls and steel bars, reminding us of our shared humanity.

Celebrate your gifts,

Matthew

Another good story, Matthew. I plan to investigate PJP further, if only to give a donation.